|

I am midway through

redoing a portion of my own living room floor with tile. This

is yet another step in preparation for my newest aquarium.

I didn't like the idea of the aquarium sitting directly on

carpet and, with the assistance of my father, the floor is

now complete with a 4'x 10' patch of tile. As the aquarium

nears completion the thought of the aquascaping design begins

to become a more frequent exercise for my mind. I go over

the details with the old man <again>, and he jokingly

quips that I should tile the bottom of the aquarium. In a

feeble attempt to humor Dad, I inquire as to why I would do

that. No sooner did I question his rationale than I had an

inner feeling of regret. Surely, I had been set up. Although

I was unsure of the reply I would receive, it did not catch

me off guard.

"So you can have Tilefish, of course!"

was his retort.

<Sigh>

Despite my father's humor taking a hit

from spending so much time babysitting his grandchildren,

he did at least plant the Tilefish nugget into my noggin.

So, in honor of bad humor everywhere, I would like to review

the Tilefish of the marine fish genus Hoplolatilus

this month, and follow-up with a discussion of Malacanthus

next month.

Meet the Family

All Tilefishes fall

under the family name of Malacanthidae. This family name has

been divided into two subfamilies, Malacanthinae and Latilinae.

It is unlikely that I will feature Latilinae in another column

as they are most often used as food fish, but I will instead

follow the path laid by the Sand Tilefishes or rather, the

subfamily Malacanthinae.

Malacanthinae, naturally called the Sand

Tilefish subfamily because all 14 species relate to the seafloor's

open sand, contains the two genera which will be featured

in the next two editions of this column. Hoplolatilus contains

11 species as noted below.

|

Malacanthidae

- Latilinae

- Malacanthinae

- Hoplolatilus

- Asymmetrurus

- Hoplolatilus

- chlupatyi

- cuniculus

- fronticinctus

- geo

- luteus

- marcosi

- pohle

- purpureus

- starcki

|

|

The above list began taking shape in 1887 when Gunther made

the genus' first description by discovering and discussing

Hoplolatilus fronticinctus. Information about the genus

or any new species remained mostly unheard of, other than

the occasional unidentified postlarvae collected in nets,

until Smith (1963) discovered H. fourmanoiri in Vietnam's

waters. Subsequent discoveries soon followed with further

underwater exploration.

The first publication to take the work of Gunther (1887),

Smith (1963) and Fourmanoir (1965, 1969, 1970, 1971) a step

further was the work of Clark and Ben-Tuvia (1973), which

also described a subgenus of Hoplolatilus - Asymmetrurus.

Whereas Asymmetrurus is known to have 25 vertebrae

and a prolonged upper lobe on its caudal fin, the subgenus

Hoplolatilus has 24 vertebrae and a forked caudal fin.

The studies of Clark and Ben-Tuvia (1973) were further expanded

upon by Randall (1974) when he described two new species along

with his genus revision, but this reference quickly became

outdated by the discovery of several new species. Burgess

(1978) described two additional species, not to mention Randall

partnering with Klausewitz et al (1978) to re-align

the genus even further. With continued exploration into deeper

waters than was previously possible, two more species were

added before the final addition of H. pohle by Earle

& Pyle (1997).

|

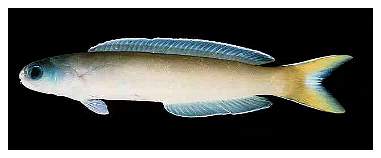

A uniquely beautiful and appropriately named Hoplolatilus

is the Skunk Tilefish, Hoplolatilus marcosi.

Unfortunately, its deep natural home range, which starts

at 100' and drops from there, generally makes this Tilefish

a rarity in the hobby. Those that do arrive in the trade

typically suffer not only from decompression sickness,

but also from an inflated price tag. This is a misfortune

to hobbyists because at four inches of length as adults,

they are a great size and make an attractive addition

to many home aquariums.

|

|

Photo

courtesy of John Randall.

|

In the Wild

Hoplolatilus

species do not stretch into Atlantic waters whatsoever, and

are completely confined to the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

The Philippines must maintain some prime Tilefish "real

estate," as their seafloor maintains quite a diversity

of species. The majority of Hoplolatilus can be photographed

around the Philippines and most of Indonesia. The few species

that inhabit outlying areas are H. luteus, which has

been recorded in Flores and possibly Bali; H. purpureus,

which stretches into the Solomon Islands; and H. starkii,

possibly the genus' most geographically diverse species, which

is found within a circle encompassing Marianas to the north,

the Pircairn Group to the east, New Caledonia to the south,

and finally over to Celebes to the west. Hoplolatilus cuniculus

is the lone South African resident, H. fourmanoiri

is the lone Vietnamese dweller, and no species is found in

the Red Sea.

Deeper locales, which require scuba diving

for effective research, are most often in Sand Tilefishes'

shallow range. This obviously accounts for the majority of

the species being discovered and described after 1970, and

continuing into the 1980s and '90s with continued deeper explorations

allowed by advanced diving technology. Although certain species

such as Hoplolatilus cuniculus can be found in 10'

of water or less, the norm starts around 60 feet for the subfamily

and continues downward to 300' to 400'.

|

|

|

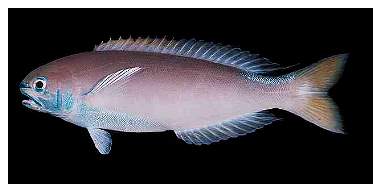

A Bluehead Tilefish, Hoplolatilus starcki. Photo

courtesy of Greg Rothschild.

|

Open sand stretches are key for this genus;

the subfamily wasn't tagged with the moniker "Sand Tilefish"

because they relate to rockwork. All species except Hoplolatilus

fronticinctus build a burrow into the sand, where they

retire in the evening or hide from potential predators. The

burrows are not made entirely of sand, however. The majority

of the burrows are erected with rubble - and therein lies

their problem. Their search for suitable rubble fragments

is a never-ending chore. In contrast, Hoplolatilus fronticinctus

collects rubble from nearby locales and constructs its burrow

entirely from this material. These Tilefish are believed to

be unable to bury themselves into the sand because they are

heavier bodied than the other species, which may make it more

difficult for them to get under the sand. Regardless, they

are master architects, building elaborate mounds of rubble

in the open sands which serve as their home.

Obtaining the rubble required for construction is perhaps

entertaining for divers to watch, but no doubt frustrating

for the participants involved. The rules are simple - all

rubble is fair game no matter where it is located or who is

tending it. Stealing rubble from conspecifics is not only

attempted and moderately successful, but it seems the preferred

method more often than not. Jawfish, gobies and just about

any other den builders are also at risk of losing their accumulated

rubble. The burrow is never finished being built; every morning,

sometimes even after returning from a rock hunting trip of

their own, there is rubble to replace. In the Tilefishes'

world each day remains simple: eat, tend to den, mate, sleep,

repeat.

The routine described above is a perfect lead-in to three

required topics of discussion, and I'll begin with eating.

Tilefish are planktivores that feed several feet above the

seafloor. They spend any time not used in their search for

rubble to hunt for food. This is done by hovering from 3 -

10' above their burrow facing directly into the current, and

the water's flow brings prey items to the Tilefish. One gut

analysis performed on Hoplolatilus starcki showed that

copepods represented 31% of their diet, an additional 31%

consisted of pelagic tunicates, and the final portion was

occupied by fish eggs at 28%. A gut analysis of Hoplolatilus

cuniculus showed that 58% of their diet consisted of copepods,

20% was siphohophores, 20% larvaceans, and only 2% fish eggs

(Randall and Dooley, 1974). Despite Tilefish being planktivores,

aquarium observations have shown H. fourmanoiri to

utilize "hydraulic jetting," a hunting method whereby

the fish spits a jet of water into the sand bed to search

for crustaceans harbored within the substrate.

Little is known in regards to the Hoplolatilus

species' reproductive nature. Besides some scientific collections

of pelagic juveniles, and observers thereby making the connection

that Hoplolatilus are pelagic spawners, science otherwise

remains mostly in the dark on their reproductive behavior.

They are not known to be sexually dimorphic or dichromatic

(Michael, 2004).

Allow me to get back to the den to finish up this portion

of the column. I have discussed how it is built and how large

it can become, but I did not really touch upon its exact purpose.

As might be obvious to seasoned hobbyists, this den is purely

for protection from prey. Tilefish are not bold fish. In fact,

they are anything but bold. At the first sign of danger Tilefish

will drop to the seafloor alongside the entrance to their

den. If the danger does not dissipate, the threatened Tilefish

will disappear into the den quicker than a diver can blink

his eyes. Only after the perceived threat has vacated the

immediate area will the Tilefish once again extend themselves

outside of their burrow to survey the situation. Finally,

and presumably so, the Tilefish retire each evening into their

burrow for a safe and peaceful night's sleep.

In the Home Aquarium

If I were asked

to describe Tilefishes' care in the home aquarium with just

one word, I would have to consider "delicate"

to be the word of choice. Great care must be taken to ensure

their prolonged success. The reward is well worth it, however,

due to the exquisite beauty of some species, the interesting

characteristics of all subfamily members, and the natural

biotope that can be created by starting with Tilefish.

|

|

|

Given their diminutive size and lack of a natural defense,

the small Sexy Shrimp stands little chance of long-term

survival in an aquarium with an established pair of

Tilefish. Photo courtesy of Greg Rothschild.

|

Fellow aquarium residents are a good place

to start the discussion of what I mean by "delicate."

Any fish going into the aquarium must be as peaceful, or more

so, than the Tilefish. Tilefish spook easily, and fast swimming

tankmates will tend to evoke a fright response in Tilefish

more often than not. Surgeonfish, large active wrasses, butterfly

fish and larger angelfish can all be crossed off the list

of potentially suitable tankmates. Adding fish with swimming

and feeding tendencies similar to the above species should

be avoided, as well as any fish that gets larger than the

Tilefish, for that matter. Ideal tankmates would be small

gobies, jawfish, flasher wrasses, pipefish, comets and dragonettes.

Corals are typically not at risk unless they are small fragments

not secured properly. In that case the coral fragment will

likely become a brick in the construction of the tilefishes'

burrow. Mobile invertebrates are safe other than with the

rare rogue individual who didn't read the same books and websites

as the rest of his cousins. Even in this instance, only the

smallest of ornamental shrimp are at risk.

Compatibility

chart for Hoplolatilus species:

| Fish |

Will

Co-Exist

|

May

Co-Exist

|

Will

Not Co-Exist

|

Notes |

| Angels,

Dwarf |

X

|

|

|

Add

the Tilefish first; ensure the dwarf angel is a juvenile.

|

| Angels,

Large |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened. |

| Anthias |

|

X

|

|

Assuming

a large enough aquarium is provided. Add the Tilefish

first. |

| Assessors |

X

|

|

|

Good

choice provided enough rockwork is available for Assessor.

|

| Basses |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened.

|

| Batfish |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened.

|

| Blennies |

X

|

|

|

Add

the Tilefish first; watch for aggression from large blennies.

|

| Boxfishes |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened. |

| Butterflies |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened. |

| Cardinals |

X

|

|

|

Good

choice. |

| Catfish |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened.

|

| Comet |

X

|

|

|

Good

choice assuming enough rockwork is present for the Comet.

|

| Cowfish |

|

X

|

|

Generally

peaceful, but perhaps large enough to frighten Tilefish

as adults. |

| Damsels |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened.

|

| Dottybacks |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened.

|

| Dragonets |

X

|

|

|

Good

choice. |

| Drums |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened. |

| Eels |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened. |

| Filefish |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened.

|

| Frogfish |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened.

|

| Goatfish |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened. |

| Gobies |

X

|

|

|

Good

choice. |

| Grammas |

|

X

|

|

Add

the Tilefish first; ensure enough rockwork for the Gramma.

|

| Groupers |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened. |

| Hamlets |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened.

|

| Hawkfish |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened.

|

| Jawfish |

X

|

|

|

Good

choice. |

| Lionfish |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened. |

| Parrotfish |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened. |

| Pineapple

Fish |

|

X

|

|

A

peaceful nocturnal fish, but it requires more rockwork

than normal for a Tilefish aquarium. |

| Pipefish |

X

|

|

|

Good

choice. |

| Puffers |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened. |

| Rabbitfish |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened. |

| Sand

Perches |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened.

|

| Scorpionfish |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened. |

| Seahorses |

X

|

|

|

Good

choice. |

| Snappers |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened. |

| Soapfishes |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened.

|

| Soldierfish |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened.

|

| Spinecheeks |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened.

|

| Squirrelfish |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened.

|

| Surgeonfish |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened. |

| Sweetlips |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened. |

| Tilefish |

|

X

|

|

Avoid

Malacanthus species. |

| Toadfish |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened.

|

| Triggerfish |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened. |

| Waspfish |

|

|

X

|

Not

a good choice as the Tilefish will be harassed or frightened.

|

| Wrasses |

|

X

|

|

Add

the Tilefish first; choose only small, peaceful wrasses. |

Note: While many of the fish are listed

as possible tankmates for Hoplolatilus species, you

should research each fish individually before adding it to

your aquarium. Some of the mentioned fish are better left

in the ocean or for advanced aquarists.

The ever popular 75 or 120-gallon aquariums

are a great size for housing these fish. Several individuals

will coexist with other small and peaceful tankmates in relative

harmony. In fact, it is important to maintain Tilefish in

pairs or small harems, so when choosing an aquarium, the tank's

size and the ultimate number of inhabitants should be taken

into consideration. Always take caution to add the Tilefishes

simultaneously or as close to simultaneously as possible,

because once they are acclimated for extended periods, they

may not take kindly to new neighbors.

|

With a trade name to match its pedestrian coloration

the Pale Tilefish is not exactly the best looking Tilefish

species for an aquarium. At least three distinct color

variations exist, but none of the three stands out from

the others in terms of beauty. As with most Tilefish,

Hoplolatilus cuniculus is best kept in pairs

in an aquarium. Photo courtesy of John Randall.

|

For ultimate success with this genus, the

aquarium's decoration is of the utmost concern. The majority

of the aquarium should be an open sand bed with extensive

amounts of rubble available for piling. Any rockwork utilized

in the aquascape should be for the benefit of its fellow aquarium

dwellers, and not the Tilefish. Obviously, this area should

be made as small as possible to make the featured species

most comfortable. In addition to having a plethora of rubble

available, large, flat pieces of rock laid upon the sand will

be promptly put to use. Naturally, a deep sand bed must be

implemented; one at least 6" deep would be a good start.

Prior to the Tilefish's addition it's a good idea to create

your own rubble mound, thereby giving the newly added fish

an immediate place to dart. In the coming days as the newcomers

settle in, they will begin the arduous task of reshaping their

burrow on a daily basis.

|

|

The beautiful Hoplolatilus purpureus, the Purple

Tilefish, seen here in a home aquarium, is known for

being a tad skiddish. Photo courtesy of Richard Cantisano

of Ramsey, NJ.

|

Acclimation is typically slow as this species

will remain skittish in its new setting for several days.

Keeping other small dither fish in the aquarium will help

facilitate the acclimation process, but still, a few days

should be considered normal. Additionally, brightly-lit aquariums

may inhibit the acclimation process as most tilefish are deep

water species. Stony coral aquariums are, therefore, not ideal

places to house Tilefish.

Food is a rather easy topic to discuss

for this species. As planktivores, Hoplolatilus species

feed directly from the water column. Early in the acclimation

period it may be prudent to feed live gut-loaded brine shrimp,

but hopefully once acclimation has progressed, a switch to

frozen/thawed foods will be possible. Moving to frozen/thawed

brine would be a good first food to switch to, but a more

solid staple in their diet would be Mysis species shrimp.

Over time the Tilefish will soon begin to recognize most items

added into the water column as food.

Perhaps the most important concern with

all Tilefish, and any fish which is easily frightened, for

that matter, is a securely fashioned, tight-fitting lid on

the aquarium. At any given moment the Tilefish may become

scared and launch itself skyward. Without a good lid on the

aquarium, the hobbyist should expect to find fish jerky sooner

rather than later. This is one point I cannot stress enough.

Get a tight-fitting lid over a Tilefish aquarium!

One last important tidbit to mention is

the Tilefish's likelihood of suffering from decompression

problems resulting in a ruptured swim bladder. Any Tilefish

exhibiting difficulty hovering in the water column is a likely

candidate for this malady, and thus should be avoided at all

costs. Although I hopefully do not need to mention this, also

be sure to watch the fish consume food added by a store employee,

and give it a thorough visual inspection prior to purchase.

The fish's failure to eat or any signs of injuries or abnormal

growths should certainly eliminate its consideration for purchase.

Meet the Species

All of the species

have a difficult time reaching 6" in length, and only

one truly has a chance to succeed. Hoplolatilus fronticinctus,

adorably named the Stocky Tilefish due to its larger than

average size for the genus, may reach 8". Perhaps as

a stroke of luck, this is an uncommon aquarium ornamental

and is rarely offered for sale in the trade. If you are lucky

enough to find one, try to acquire several. In the wild they

live in small groups occupying burrows which infringe upon

one another. Furthermore, a pair often occupy the same burrow,

so purchasing this species as a pair would be ideal.

|

The largest of the Hoplolatilus species is H.

fronticinctus, measuring in at roughly eight inches

as a full-grown adult. Undoubtedly, many hours of thought

were given prior to awarding it the trade name of Stocky

Tilefish! Their large size also means that they accumulate

a large pile of rubble - often measuring over 160 square

feet. This is a difficult species to track down for

the aquarium, perhaps rightfully so given its requirements

for such a large rubble mound. Photo courtesy of John

Randall.

|

|

A deep home range keeps the Green Tilefish

from becoming more popular in the aquarium trade. One hundred

feet is generally where a diver can begin to encounter Hoplolatilus

cuniculus. This species is often found upon silt or even

mud flats, in slight contrast to its kin.

Arguably the most attractive member of

the genus is also one of its most delicate. Perhaps it is

just me, but from my observations it seems like this is the

case regardless of genus. Regardless, the Skunk Tilefish,

known scientifically as Hoplolatilus marcosi, is a

real gem if you can track one down. Again, obtaining at least

a pair would be ideal. Like most members of the genus, their

preferred deepwater habitat of 100' or deeper inhibits their

availability, but don't fret; they are available if you look

long and hard enough.

Another show-stopper of a beauty is Hoplolatilus

purpureus. Naturally, from the Latin name you should be

able to infer that this species is purple, but of course Mother

Nature didn't give it a drab palette of a single purple color.

Hues of blue, red and purple blending into a hot pink entertain

the eyes and make for a desirable and attractive aquarium

resident. The Purple Tilefish exhibits the same problems as

most of the genus: its deep water collection sites and a delicate,

if not outright nervous, persona.

|

Certainly one of the more attractive members of the

genus is Hoplolatilus purpureus, the Purple Tilefish.

At an average size for the genus (five inches) it can

be adequately housed in a 100-gallon or larger aquarium.

Like most Tilefish, and any deep water fish for that

matter, the plum pretty Purple Tilefish may typically

suffer swim bladder infections. Only after extended

careful observation should a pair be considered for

purchase. Photo courtesy of John Randall.

|

Perhaps the most regularly available species is Hoplolatilus

starcki. The Bluehead Tilefish, although still delicate

and requiring peaceful tankmates, is also perhaps the most

aggressive member of the genus. It maintains a greater distance

between conspecifics than any other member of the genus, and

is not afraid to chase conspecifics if they venture too close

for comfort. Nevertheless, a pair should be obtained if possible,

to better the success of acclimation.

Coming Next Month

In Part II of the

Malacanthidae feature I will conclude the discussion of Sand

Tilefish. Malacanthus will be under the spotlight as

I detail how, despite being close cousins systematically,

the two genera of Sand Tilefish are still very much their

own genus.

|